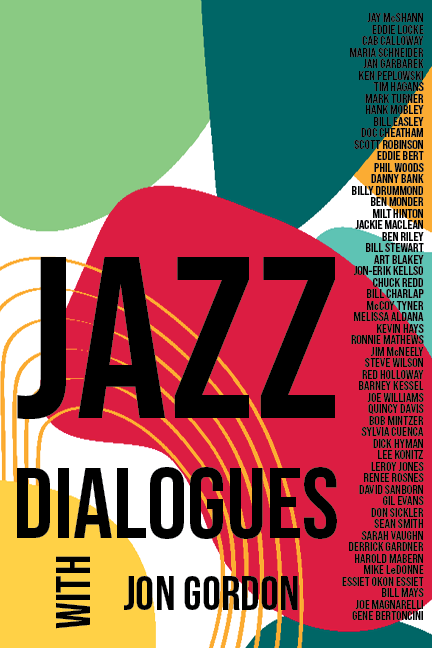

The jazz world recently lost a beloved and spectacularly talented musician, Ken Peplowski. In honor of Ken, we’re happy to share this conversation with Jon Gordon from his Cymbal Press book, Jazz Dialogues. We hope you enjoy it. Rest-in-Power Ken.

Ken Peplowski

Japan – 2013

JG: So, Ken Peplowski. First of all, I’ve got so much respect for you and what you do. When I was 19 and you were 27, we met working in Loren Schoenberg’s band. You’re now 39 and I’m 53. I don’t know how that happened exactly. You’re a great saxophonist and musician. But in my opinion, you’re the greatest living jazz clarinetist in the world. And the great Danny Bank agreed as well and told me one night on a gig with Loren Schoenberg’s band in ’86 or so, “Ken’s the greatest clarinet player in the world.” And that’s pretty amazing coming from him. Have I blown enough smoke at you to start the interview?

KP: [Laughter] Well, just to blow some back… you know, it’s funny in New York. There are so many different paths you can go down, so many circles of musicians. Unless you live there it’s hard for people to grasp the concept that you can have people that you consider your friends and colleagues and never see them for long periods of time. But I never forget. I remember all the guys that play good. The thing in everybody’s playing that I admire is when your playing is an extension of you. If you’re an honest player, that’s what grabs me. No matter what the context, I want guys that show up, give of themselves and get into the spirit of the music, no matter what it is, and that’s what you do.

JG: Well I appreciate that, thanks. To me, it’s a learning experience to go into various situations. I love hearing the history of the music in people’s playing and I certainly hear that with you. On this tour it’s Benny Goodman music, Fletcher Henderson arrangements, and some others. But when you play that extended solo on “Sing Sing Sing” you can go any direction. It’s just you and the drums, and the sax section just looks at each other and smiles every night.

KP: Well, that’s great. I’m doing it half for myself and half for the band. I’m not trying to impress the band members. I’m trying to completely open up and whatever comes into my head—whatever happens, happens. In a way, that might impress the band members, when everything’s flowing like that and you’re creating something different. I could just play over A minor and do a real cliched thing. But if I’m going to do a job like this, within these musical parameters, I just don’t want to play musical dress up.

In fact, my way of researching when I go into a long gig like this is by not listening to Benny Goodman. All the tempos, the phrasing stuff, I’ve changed a lot of things from how he did it to how I want, but that’s out of respect to him, because it was a malleable music to him too and he never thought of it as nostalgia. It was just great music to him, and he thought about those charts and edits to make over a long period of time. I think, though no one can speak for him, but I think he respected musicians that came to the job with respect for him and the music but didn’t try to imitate him. He didn’t want the drummer to try to play like Gene Krupa! Then it just sounds like a bad parody.

By the same token, if somebody calls me to do something I wouldn’t normally do, like a more Coltranesque thing or an avant-garde thing, I just use what I’ve got and put myself into that music. You have to be yourself in a slightly unfamiliar setting. They’ve called you because you must have something to offer. All you can do is be the best yourself you can be, that’s it. If you try to do something else it’s going to sound forced and false. And I have to sometimes remind myself of that when I’m in a slightly different setting, and just play my own way and try to find a way into something different.

JG: I feel the same way. You can’t over think it. The only thing that works is where you’re just in the moment. Eddie Chamblee, one of my musical fathers, told me his musical and life philosophy was essentially, “Fuck It!” It sounds simplistic, but particularly in a musical context with what we do as jazz musicians, “Fuck It,” let go of judgement, be in the moment.

KP: One thing I’ve learned is to also think of recording that way. A recording is literally how you performed on that day. If you remember that and not get too hung up about it… you have to get some distance and try to listen as though it were someone else’s record instead of worrying about every single note and micro-managing it. And also, as you get older—I’m not getting older of course—but you are and I’ve noticed this in you. [Laughter] But as you get older, you just tend not to care so much about what other people think.

JG: That’s a good point. Dick Oatts told me one time when we were on a gig together, “At a certain point you just stop worrying so much about whether it sounds good, and it’s just better, because you’re more in the moment and you’re not judging yourself.” On a similar note, I sometimes talk to students about the process of composition and arranging because it allows you a different kind of creativity than just being in the moment as we need to do as players. You can think about music the way a sculptor or painter or playwright does, and you can deal with it for months or years and make changes to it over time, along with the in-the-moment process, like Jackson Pollock throwing paint on the canvas.

KP: That’s my goal at times with standards. I revisit songs that I’ve done for a long time and am still chipping away the sculpture of that song. I think about people that have inspired me, Benny was one, Sinatra, Bud Powell. Sometimes it’s great to step away from tunes and come back with a new concept. But Lee Konitz has been playing “Pennies from Heaven” for…

BOTH: Seventy years! [Laughter]

KP: But it’s fresh every time.

JG: Yes.

KP: You notice on my gigs, for example, if we’re playing older music, I never ask anybody to do anything stylistically. You’re all smart players. If you love what you’re doing, you find a way in and to make it your own. The solos played now couldn’t have been played in 1939. That’s a great thing. It’s a way of treating this music so that it’s not a nostalgia piece.

JG: You and Jon-Erik Kelso just hipped me to this live version of Benny on “Stealing Apples” that’s incredible. And that was the arrangement we did with Loren’s band.

KP: Was that at the Cat Club?

JG: Yes! So many great players! Mel Lewis, Eddie Bert, Bobby Pring, Britt Woodman, Eckert…

KP: Dick Katz…

JG: That arrangement and your solo really blew me away when I first heard it. So, I did want to ask you about how you got into music and the clarinet.

KP: Well, I fought with my family about just about everything. My dad was a conservative cop in Cleveland. I went the other way. But the only liberal quality in my family other than my outlook, was music. They really liked to listen to all kinds of music. Maybe that whole generation was that way. As an aside, I find it interesting that now a lot of younger people are strangely conservative that way. Maybe they’re conservative in other ways as well. But they just limit themselves to a certain thing, though they have many more choices than we had.

JG: I wonder if it’s because they feel overwhelmed by the choices? Miles said something about that in an interview in the ’80s. There’s more music to be aware of, to assimilate now, to find your own thing than there was when he was coming up.

KP: Could be. And there are scientific studies showing that people’s attention spans are getting shorter. So, they’re a little intellectually lazy now too, and they don’t take the time to seek out other things. Just because they’re swamped with Twitter and everything else. But anyway, I remember my family went to see A Hard Day’s Night in the theater in 1964. I was born in 1959 and was five years old. I still remember the girls screaming. And back then I thought, “There’s something in this that I want to do.” Also, from an early age I liked to make people laugh. I got up in front of the class and made kids laugh. I’d make up jokes, routines actually. So, there’s something in there. I just like that connection with an audience. I was shy otherwise, but it was my way of making friends. To some degree I still am actually and often just stay holed up in my room on these kinds of tours.

JG: Me too. Well, this band and most of the bands I’ve worked with, it’s a great bunch of people and that really helps.

KP: It is. And you do feel relaxed with them.

JG: It makes you want to reach out more, instead of just sitting in my room and eating a meal bar.

KP: Yeah, me too! Exactly. Back in New York we rarely go out, we just like to stay home a lot. So, going back, when I was a kid, I had all kinds of problems with my home life, but I learned how to use art as therapy from an early age. I was a voracious reader. I liked to draw cartoons, and I loved music, though I hadn’t played it. As a kid I always thought that I was self-aware. That doesn’t necessarily mean smart. But I could talk to myself, reason with myself, and think to myself with all the problems at home, “Someday I’m going to get out of here so I can deal with this.” I had a couple friends in school, not many. But if I could make kids laugh, I’d reach out to them. I was popular, but I didn’t socialize much. But, from an early age, I wanted to be a writer, an artist, or a musician. Now, my father was an amateur musician.

JG: What did he play?

KP: Well, he first tried to play trumpet, gave it up in frustration, and then gave it to my brother who was two years older than me and became a trumpet player. Then he tried to play clarinet. He gave that up in frustration, I got the clarinet. But if I’d been the third son, I’d be an accordion player today! [Laughter] Thank God for that, because that was his next instrument!

JG: This would be a very different kind of tour…

KP: Yes. You know, Polish community. I loved the clarinet from the beginning. I guess I was ten or eleven when I started. Within a year, my brother and I had a polka band, playing at weddings and dances, going on local TV shows. He was two years older, that sibling rivalry, you know? And he was a hot shot when we were growing up and I wanted to be as good as him or better right away. This was interesting too, this breaks all the rules.

My father would sit and watch us, arms crossed, making us practice, critiquing us. And that destroys many people. But I kept thinking “Fuck You!” Or the equivalent when you’re eleven. But I thought, I’m gonna try to get so good that he can’t say anything to me, and, I’ll be outta here. And as soon as I started playing in a public forum, weddings, and dances, that was it for me. Playing music for a living. Instantly I knew that was my path. My father incidentally, never, ever, paid me a compliment. Ever.

JG: Wow.

KP: Up until literally when he was on his death bed. And then he said he was proud of me. But I headlined in Cleveland with Terry Gibbs on one half, I was on the other, with the Cleveland Jazz Orchestra. It was 1985, ’86. And my father’s only comment was “You squeaked on the second song.” I’d just walked off to a standing ovation.

JG: Wow.

KP: So that was that. But I just turned it inward and put it into my music. Which has been the greatest therapy for me in my life.

JG: Probably for most of us, right? I found a lot of people along the way that said, “Music saved my life.” You realize what a blessing it is. Here we are in Japan, we get to express ourselves, see the world, and share our love of music through playing, writing, teaching…

KP: And with all of those ways, you do feel once in a while that you may have moved somebody. You learn how to satisfy yourself too. But it does mean something to get that reward, or acknowledgement, or just the good feeling that you’ve made an impact on somebody else.

JG: Well, in most places outside of the states, people are really appreciative of music.

KP: Well, it means something to them too, it’s not just a functional thing, like listening as background music while you’re doing something else. And you know, everybody that ever said they don’t care about the audience, bullshit! If that was the case, you wouldn’t be in a public forum. You’d just sit in a room and not do a thing or try to submit it to anybody. Everybody cares. Miles Davis cared. Why did he dress that way if not to impress people?

JG: I agree. So, who were teachers that were very important to you?

KP: I was very lucky to have some great teachers in junior high and high school. I had this one band director in junior high. And I don’t know if he really believed in me or if he was frickin’ lazy, I don’t know. [Laughter] But he had me write and arrange one of those school pageants with multiple performers for the whole school orchestra. I knew nothing about writing like that!

JG: How old were you?

KP: Oh my god! This was eighth or nineth grade.

JG: How did you do it?

KP: I got a book on arranging. I read about the ranges of the instruments. I would spend hours and hours at home reading. I taught myself how to play piano, in a backwards way. I learned the notes. I used to stack and write notes on top on one another without knowing what to call the chords, C7, etc. Then I learned the theory later. But in a way that’s a good way to learn because you’re learning by ear, intuitively. It probably didn’t sound good, but I did it! I wrote an arrangement of “Smoke on the Water” by Deep Purple. [Laughter]

JG: Wouldn’t you love to have that released! Ken Peplowski’s arrangements of your favorite rock hits of the ’60s!

KP: Yeah, greatest shits… I wrote some Stevie Wonder thing for the jazz band.

JG: Great!

KP: But real encouraging teachers! They were so hip for their time in Garfield Heights, Ohio. First of all, they would encourage us to play our own solos, to bring in things. We would listen to records. I had this teacher, Thomas Husack, we were playing Don Ellis arrangements in junior high school!

JG: That’s amazing.

KP: Because they believed that we could do it, and we did it! Now I go to schools and they can barely get through “In the Mood.” It’s unbelievable. It wasn’t all talented kids, but somehow, we rose to the level of where they thought we could play at. I had another guy in high school like that, that let me be free to do my thing. I was always a pretty good student, A’s, B’s… I’d get out of classes to go to the music room and play piano all the time. Here’s another weird thing—maybe because of my reading lots of books—I could always just sight read anything. Don’t ask me why. I’d never practice my lesson, but I’d play like crazy, practicing everything but my assignment, and then go and sight read my lesson. I spent so much time in the band practice room. I even got good at forging the band director’s signature on notes excusing me from Spanish or math class, and they’d always buy it! But I was always doing something—the music for a school play or something.

JG: Did you have a great private teacher?

KP: I did by high school. This guy was the clarinetist with the Cleveland Ballet. By this time, I’d been playing saxophone too. ‘Cause the necessity of playing weddings and dances, you graduate to saxophone as well, everybody does this. I think I got a tenor and alto at the same time and was going back and forth. And I loved that for the different texture. Even back then, I never thought of myself as a doubler, and I never have. I just try to approach the instruments as two different entities, and what’s different about each of them and not find shortcuts. Anyway, so this guy, my private teacher, Al Blazer…

JG: What a name…

KP: Yeah, I know. Kicked my ass! He was so tough! Literally reduced me to tears. And again, like the experience with my father, except he basically told me I was playing wrong, wasn’t breathing right. He basically tore apart everything and had me start over again. He told me from the first lesson, “Hey, you’re unbelievably talented, but I’m going to be really tough on you.” And he was! And again, I just went, I’m gonna try to fuck this guy up, and started practicing the lessons. He was an interesting guy.

Just to skip forward… I went to Cleveland State University, just to keep studying with him, ’cause he was such a great teacher! But his students in college, if they didn’t give him anything and didn’t give a shit and weren’t even trying, he’d send them out for sandwiches, that kind of thing. But me, he continued to be really tough on me, and man I’ll be forever grateful to that guy.

JG: What did he have you work on? Was it a lot of the classical repertoire?

KP: Mostly classical repertoire.

JG: Have you performed much of that? I’m sure you could go out tomorrow and play a whole night of that.

KP: I wish that were true. But I do like to play that music and sometimes do. I actually recorded with a symphony in Bulgaria. We did the Darius Milhaud concerto, a great piece of music. Not widely known or recorded. And we did the “Lutoslawski Dance Preludes”—great pieces.

JG: Wow, I’d love to hear that, I’m a big Lutoslawski fan.

KP: I’ll send it to you. I also had a conception of doing Ornette Coleman’s “Lonely Woman” on that record, and I wanted to have the orchestra improvise too.

JG: I love getting classical players to improvise! They don’t know they can do some stuff until they do it. You tell them, “You know the scales, it’s just two chords, go for this here,” etc.

KP: On this one, we gave them little passages. I brought a quartet over with Greg Cohen, and the conductor would cue one of these passages at random, out of time… based on what we were doing. That was my way into that. And it worked well actually. We talked about this the other day. I’ve got a few people I like to work with. I let them do the writing, but I sketch out the ideas. It was my concept, but Greg Cohen wrote it. Regarding classical music, I really have to work hard at it. Last year I did a concert with Ted Rosenthal. And I put a movement of the Poulenc clarinet sonata on my last record, with Ted.

JG: Well I’m on that record with you of James Chirillo’s piece.

KP: The concerto.

JG: I knew and loved James’ writing but didn’t know his through composed stuff and really loved the piece. You sound great on it, and it reminded me a bit of Stan Getz on Focus. I thought it was a great vehicle for you and was great to hear you in that context.

KP: My guy, before Benny, was Jimmy Hamilton. And the reason I loved him is because he had one of the most beautiful sounds of all time. He could have easily played in an orchestra. He had that beautiful, classical, round, sound—loved it! And on clarinet, no matter what style of music you’re playing, why do you have to sacrifice the sound, tone, and pitch just because you’re playing jazz? I hear so many people play clarinet, and they try, for lack of a better term, to play “funky” like the great New Orleans clarinetist George Lewis. And he was great, but that was his thing. All these schooled players, trying to sound unschooled, trying to play saxophonistic, dropping their beautiful sounds, all those scoops that don’t quite get back up to pitch… you have to cut that in half on the clarinet and use more grace notes. But Jimmy Hamilton had that wild exotic semi-classical sound on all that stuff that Duke and Strayhorn wrote for him.

JG: Some of the stuff on the suites.

KP: Oh my god! That really grabbed me! Even before Benny.

JG: Since we’re talking about your favorite clarinet players…

KP: Well all of Duke’s guys. Barney Bigard, Russell Procope, Jimmy Hamilton… the whole world of Ellington. I just thought, this is what jazz is all about.

JG: And clarinet is so essential in Ellington’s music.

KP: Yeah. But even on tenor, listening to Ben Webster, Paul Gonsalves, even Jimmy Hamilton playing a kind of R&B based tenor in a way… what variety of sounds and approaches! Johnny Hodges… I always tell people, the whole history of jazz is there in Ellington, more than anybody else. So those guys, Duke’s clarinet players. There was a whole school of the New Orleans guys… Edmund Hall, Albert Nicholas, Pee Wee Russell, Jimmy Noone… but mostly Benny, Duke’s clarinet players. And then everybody else that I listened to was sax and piano players.

JG: But the other day you also mentioned on your short list… John Carter.

KP: John Carter! Oh, that guy! Oh yes! Well, I was always intrigued by Ornette’s music. You and I have talked about this. I think he’s one of the most melodic players of all time.

JG: Yeah. You hear a lot of history in his sound, approach, and the way he plays melodies.

KP: I’m a sucker for melody. I’m not saying that’s the only approach, but that grabs me. And Ornette has that, in my mind. And John Carter… I think I heard him on the radio, probably in Cleveland. He had a quartet that modeled itself after Ornette, with Bobby Bradford on cornet, bass and drums. I apologize that I forget their names. But very much modeled after Ornette’s band, similar songs, form, everything. A beautiful sound on clarinet! Again, he kept this great sound, even while playing more avant-garde free jazz. He was also a good saxophonist too. Later, he did some experimental things with synthesizers. I took some electronic music courses where there were no keyboards, just waves of sound.

JG: Theremin or something?

KP: No, just old-fashioned knobs and electronic sounds, and coming up with compositions based on that, no notes. John Carter did records like that. I always found that fascinating. He was another guy that opened up a whole word of possibilities for me.

JG: So, how long were you in college?

KP: Two years at Cleveland State. But then I played a jazz festival with a quartet. It was me, the Teddy Wilson trio, and the Tommy Dorsey band.

JG: You played with Teddy!?

KP: No, though I did sit in with him once. There was a place in Cleveland, Chung’s I believe. The piano player there, Larry Booty, would bring in these more traditional musicians.

JG: Another great name…

KP: Yeah, sounds like a… oh well… [Laughter]

JG: That’s for a different podcast and book… [Laughter]

KP: Larry would always have me sit in with these guys, like Art Hodes, Ralph Sutton, Kenny Davern, years before I got to New York. Somebody gave me a picture of me sitting in with Kenny one time, I was like eighteen. So anyway, I was at this jazz festival in Cleveland with Teddy Wilson’s trio and the Dorsey band, and they needed a lead alto player and offered me the gig. And Buddy Morrow who led the band at the time told me he’d give me a clarinet feature each night, fifteen minutes with a quartet. So, I played on that for two and a half years before moving to New York.

By that time, it was 1981, so I was 22. Buddy convinced me to move to New York. The money wasn’t good, like all those bands in those days. But if you were making signs that you wanted to leave they’d give you a slight raise. And Buddy called me into his room and said, “I know you wanna leave. I could give you another raise. But I’ll tell you what. I’ll make it easy for you. I’ll gladly let you go. If you promise me that you’ll go to New York, and not go back to Cleveland and be a big fish in a small pond.”

JG: Wow! Good for him!

KP: Oh my god! So, I did. He made some phone calls on my behalf. Nothing panned out. Because the last of the old guard studio guys were very protective of their turf. But it was nice of him to do it. I knew only a couple of people, Mark Lopeman being one of them ’cause he’d moved there before me.

JG: He was from Ohio too?

KP: He was, but he was from Akron. But he was also in the Dorsey band, and that’s how we met. And Lopeman called me to sub in Loren Schoenberg’s band one time, very last minute, fifteen minutes before the rehearsal. But then, I’m sure you had the same experience I did—you do one of those rehearsal bands, and you meet fifteen, seventeen guys right away, and the world starts opening up to you. Somebody calls you to do a bad wedding someplace. But in those days—I always tell this story—my first wedding job was Mel Lewis, Milt Hinton, Steve Kuhn, Bucky Pizzarelli, and the other tenor player was Buddy Tate!

JG: Wow!

KP: Kind of a weird band, but an interesting band.

JG: What a learning experience!

KP: But we’re playing somebody’s wedding! And those gigs were plentiful back then. And you’d just go through songs. Didn’t matter what you played as long as you played the right groove. You were learning how to swim by being thrown into the water. And because I had a reputation as a clarinetist too, I got called to sub at Eddie Condon’s and Jimmy Ryan’s. I didn’t really know that repertoire. I was listening to Sonny Stitt, Oscar Petersen, Benny too. But the whole traditional thing I didn’t get into until after I moved to New York, by necessity. But those guys were so nice to let me… I’d sit there and try to follow these frickin’ songs that had three or four parts and key changes… but they’d let me solo last, so I’d have a fighting chance at hearing these changes.

JG: Tell us about some of the musicians you played with at these clubs.

KP: Well, first of all, Roy Eldridge was holding court at Ryan’s. Singing, not playing any more. I remember the West End Cafe, Jo Jones was there, Sonny Greer, Russell Procope, Vic Dickenson, Dick Wellstood…

JG: He’s another guy I wish I could have heard live and played with.

KP: Oh my god! What a mind, in every way, on and off the bandstand.

JG: The first time I met Kenny Davern, I got hired to play as a soloist at twenty at the Oslo Jazz Festival. And luckily for me everybody took me under their wing. Kenny and I got friendly right away. And within about an hour of meeting and playing with him, we went for a walk in Oslo, we sat down and he told me about Dick having passed. He said to me, “You can’t believe what you just missed! This was my best friend, both musically and personally.” And just the other day I heard some Dick Wellstood that I didn’t know of, and that was some of the greatest stride playing I’ve ever heard.

KP: And a real original! Always just sounded like himself. So, there was that whole wave. Milt Hinton, Dick Hyman, who was so good to all of the younger players. He brought us into the studio scene to the consternation of all the other guys there. But I played on some of those Woody Allen soundtracks that Dick did. He hired me for all of his concerts. I think it gave him a boost to play with some younger guys. It certainly gave me a boost, getting to play with him. And then I started doing these jazz parties.

Again, I got in at the tail end of all those great players—Al Grey, Joe Bushkin, Buddy Tate, Gus Johnson, Flip Phillips, who became like a father to me—we were really tight! When my first son was born, he made a clock for him with his name made out of an old DownBeat plaque of his. And I got Flip’s practice box. He had this beautiful, hand-made carved box that he used, with all of his reeds and a tape that he used to like to practice along with. One side was Lester Young, the other side was Sinatra.

JG: Wow.

KP: Yeah. And he used to play along with that stuff. These guys, you’d show up on a gig and there’s Mel Lewis, Hank Jones… there’s Phil Woods, Al Cohn. I was shitting my pants, you know, scared to death. And they were, for the most part, pretty accepting, as long as you didn’t make an ass out of yourself. I kept having to tell myself, “Just don’t get nervous, do your thing.” I played with Jimmy Rowles a couple times. I was really intimidated by his playing. I just loved it so much, his great sense of harmony. I wish I could go back and play with him now because I felt like I was too self-conscious playing with him.

JG: Yeah, I felt that way a lot of times, I know what you mean. I think I got the tail end of what you’re talking about. I got to meet and play with some of the guys you mentioned. And I think that’s one of the reasons that I’m very appreciative of all the various scenes I work and move in, and it’s also one of the reasons why I wanted to do this book project. Students don’t have the luxury of walking in and hearing, meeting, and playing with guys like that.

KP: Or playing songs you never even heard the titles of before!

JG: Exactly. I always tell students, go and be around these guys if you can, it’s just an education.

KP: It is, and also, a lot of times there’s a glibness around students. I don’t think I was, or you were either. I think they listen to someone of an older era, like Buddy Tate, or Doc, or Zoot. And because with all of our knowledge in hindsight, of course we could duplicate their solos, their notes, a lot of players think that makes them unsophisticated, or easily duplicated and doesn’t have validity. Incidentally, Michael Brecker loved those older players. Students don’t get the beauty and the simplicity. Yes, we can play those notes, but that’s because they came up with it first, dummy! Were it not for them, you wouldn’t be standing on that foundation!

JG: Yeah, we stand on their shoulders. If something seems technically attainable some young players will think, “I know those notes, I can imagine doing that.” But they could never play them how they played them or play a ballad the way Buddy Tate did. Or approach one note the way Gene Ammons did. And I think that’s the seasoning the next generations of younger players needs to understand. The longer you play this music, the more you realize what there is to learn.

KP: It never ends, and it shouldn’t.

JG: I mentioned to some students the other day, it’s like someone’s dropped you in the middle of the Pacific Ocean and you say, OK, let’s just swim that way… it’s just vast and endless. So, trying to give some indication of that to younger players, the history, the meaning of it—it can only be a bit of a doorway. But if you follow the threads, the same way that you did, in Cleveland, and followed your passion and the people and music that inspired you, it just gets deeper and wider, and all the sudden you just realize, I’m in the middle of this infinite thing, and I’m just incredibly blessed to be around the kinds of people you mentioned playing with.

KP: Buddy Morrow said something that stuck with me forever. He said, you should always try to play with people better than yourself, and never get into a place of just hiring people that are comfortable to be with, like an old pair of shoes. You want to be challenged. You want somebody that shakes you up. Even this band, I like to pick a band that’s fun and does the music, but does it their own way. So, I’ll take any situation within… well, even without reason. And a lot of things are scary. But I’ll get in there. And all I can do is just be myself and not worry about what other people think. I always tell other musicians—sometimes they think you don’t want to do side projects for them or be a sideman. But I love that! It’s something new and different. I can find my way into this other music. I also love playing behind singers.

JG: Well that’s a lost art form in itself. Playing with and behind great singers, hearing it done in a great way. To your previous point, I had a great time playing a week with you at the Blue Note this past January, all those arrangements that Mark Lopeman did. Again, Benny Goodman is a doorway for you to get out here and to a lot of different things. But playing all those contemporary arrangements on that music was great. It was a great band—Lew Tabackin, Terrell Stafford, Willie Jones III, Monte Croft, Ehud Asherie. That’s a perfect example of what you’re talking about. Whatever you’re doing, bringing it into the current moment, keeping it fresh.

KP: I like playing with Martin Wind and Matt Wilson a lot lately. I use different piano players, Ehud Asherie, Ted Rosenthal. Those guys have a great attitude towards music and are willing to go in any direction at all. They’re very open and I love that. They get what I want to do. There’s an assumption that guys who play a lot of mainstream jazz or standards-based jazz, that you just want them to keep time and comp tastefully. I don’t want that. I always tell the rhythm section, I just want you to react to the music, and then the drummer can play as much as he wants if he’s doing that. There’s a difference between being busy in an annoying way and reacting to the music and playing the music.

JG: Let me ask you if you remember this. We did a tour of the Midwest with Loren’s band in 1989 for two weeks, doing a lot of Benny Goodman actually. There was one marquee that read, “Tonight, LIVE, Benny Goodman!” I thought, well, that’s gonna be a little tough to pull off. But we came back to New York and played the Cat Club. It was maybe towards the end of the time of when they had a swing dance night there. Mel Lewis was on drums, and he hadn’t made the tour with us, it was just a day or two after the tour.

Very rarely in my life have I ever had this crazy transcendent kind of feeling on a bandstand. Loren started to count off the band, 1, 2… 1, 2, 3, and somewhere between 3 and 4, I heard the ring of a cymbal, and it just all the sudden felt like we were on a hovercraft, just somehow floating. That whole first set! My memory of Mel when he played is that he normally kind of had a poker face. But that whole first set I kept looking back at him and he was smiling like crazy! I kept looking around at guys asking, “Do you feel that?!” And they all said, “Yeah!” Do you remember that night?

KP: I remember a lot of nights like that with Mel and having that same feeling actually.

JG: And he wasn’t limited…

KP: Not limited at all.

JG: Yeah, by anything at all. Any context, whether with Thad, or Lovano…

KP: And he always sounded like Mel Lewis. He had that beautiful sound, that different sound. But you could tell, again, when he played something, he liked it, he enjoyed it. He enjoyed those charts too. Loren never asked Mel to do anything other than to be himself.

JG: I got to play with Mel in a few contexts at that time, and he said to me when I was nineteen, “It’s really good that you’re getting the experience at your age of playing for dancers.” And so immediately you’re not just in the mindset of “I’m an artist!” You’re in the mindset of one of the functional rudiments of the music. Of course, you’re always trying to be an artist! But it’s a dance music, it should never lose that.

KP: Right, no matter what the music is.

JG: If you’re listening to Bird, or even late Trane, you still hear and feel that and the blues.

KP: That’s how you move people, sometimes literally, but even in a theater. You’re reaching out to what is a core element within everybody. Mel had the same ability that Ray Brown did. I worked with him a little bit. You’d count off a tempo, but they’d put it where they wanted it. But you couldn’t argue with them. Because it was so right, and so strong, and you just went, “Oh yeah, that’s where I should have counted it off.”

JG: Yeah. To kind of sum up, what’s on the horizon for you?

KP: Well, I’m so happy with the record I just did. I feel like it captures everything I do. I’d like to do more gigs that capture that.

JG: And I just saw an amazing review of that recording!

KP: Yeah! And that reviewer, he really did get it! You know, I recorded a Beatles song, a Beach Boys song—I wasn’t trying to be hip—those songs are forty, fifty years old. But it’s stuff that I love. I’m trying to play things that reach out to me and that I can make my own.

JG: Well, Brad Mehldau and The Bad Plus are recording things like that, why not? Wasn’t Duke’s highest compliment to describe music or musicians that were beyond category?

KP: Yeah. And when I listen to music, I listen to everything. The frustrating thing for me, and all of us to some extent, is that I feel so proud of my records. I spend about a year planning them. But I can’t then parlay that into gigs where I present that music without the strong support of a record company or an agent. I don’t have a way to get gigs doing the kind of music that I’m recording that I love. So, we’re all making all these compromises along the way to keep working and yet try to stay true to what you want to do. More and more now promoters are taking the easy way out and doing “The music of…” or “Tribute to…” instead of just letting us do our thing.

JG: Well Wynton’s made recordings with Willie Nelson and Eric Clapton.

KP: Well, everybody does that to some degree. But I wish I could get on the Euro circuit a little more. The only clubs I can do that at in New York are Kitano and Smalls, and neither pays very well. If I play Dizzy’s or the Blue Note I’ve gotta come up with a kind of theme for them.

JG: Well, I have no doubt that the next step for you is to have that kind of freedom to do what you want. It’s certainly deserved.

KP: I remember Lee Konitz telling me—he’d just won some Danish jazz prize—”All you have to do is live long enough!” But I don’t want to wait until I’m too old to not play my best. I just wish they’d meet me halfway and say, “Oh wait, this guy can play, let’s let him do whatever he wants to do.”

JG: Tell us about the most recent record.

KP: It’s Matt Wilson, Martin Wind, and Ted Rosenthal. I called it Always the Bridesmaid. Somebody asked me one of those questions that only makes you feel bad, “You’re in those polls every year but you’re always third or fourth… how do you feel about that?” What can I do about that!? I don’t have a machine to pay publicists… anyway, the recording is just songs I’m working on. I did a couple of duets with Martin Wind, a McCartney song, “For No One,” a Harry Nilsson song. On the record before this I did a free version of George Harrison’s “Within You Without You.” And we did a weekend at Smalls in preparation for the recent CD. I wanted to record without booths or separation.

JG: I love that.

KP: I used Malcolm Addy—who recorded James Chirillo’s “Concerto at Avatar”—though Malcolm works as an independent. We had three sessions booked, but we got it in three hours. I wanted an Edward Hopper painting, and they got it for the cover. One reviewer said this “is a manifesto against perfection” and I couldn’t have put it better. That’s my thing. I want that human element in the music, where you can hear and feel people breathing.

JG: I’m completely there with you.

KP: I’m not against machines. But I find that most of the music I dislike is, for lack of a better term, corporate music. Whether it’s pop, country, jazz… it’s music that pretty much is written by committees. They sit around and say, “What do we need?” and then it’s too sterile.

JG: Oh, it’s just horrific. So, what will the next recording be?

KP: The next record will be an extension of this current one. I do honestly feel that each is better than the one before and I’m proud of my records. I don’t listen to them once they’re done.

JG: But it is very meaningful to have a body of recorded work that you feel good about. I want to end where we started. To me I think you’re the greatest living jazz clarinetist in the world.

KP: I’ve got a gun on him.

JG: Is now a good time to ask about a raise?

KP: [Laughter]

JG: But I mean it. It’s very rare to say that in this music, there are so many great artists. But it’s important to me to say, especially in light of you saying “Geez, I wish I could do the music I’d like to do.” But to me you’re one of the really important guys in the history of the clarinet in jazz. So, I just wanted to put that out there, so thanks for doing this.

KP: Oh, it’s a blast. Really fun. I enjoyed it.

JG: And when you’re trying to sleep tomorrow on the bus, I’ll just keep talking at you like this until you say, “Would ya stop now? Would ya go away?”

KP: [Laughter] No, but now you got me talking again, I can’t stop… no, but next year, I’m actually doing a couple jazz camps for the first time. I’m doing John Clayton’s thing in Port Townsend. And I’ve got a week in Hayes, Kansas at a jazz camp. I like doing that and giving my own perspective on improvisation. Ultimately, I try to get students to be their own teachers and give them things I’ve honed over the years to get to that.

JG: Well I’m sure you’d be great at that, and I hope we get to do some of that together too.

KP: Thanks.

© 2021 Jon Gordon – Cymbal Press

Get your copy of Jazz Dialogues by Jon Gordon from Amazon.com in Kindle, softcover, or hardcover editions.